Build Civic Background Knowledge and Boost Engagement with Current Events Articles for Students

Last month’s U.S. election had the highest voter turnout in over 120 years despite a persistent narrative about the fragility of American democracy. The level of civic engagement witnessed is not guaranteed. Earlier this year, in his annual report on the state of the judiciary, Chief Justice of the United States John Roberts lamented civic education in the country, which he felt had “fallen by the wayside.”

“Civic education, like all education,” Chief Justice Roberts wrote, “is a continuing enterprise and conversation. Each generation has an obligation to pass on to the next, not only a fully functioning government responsive to the needs of the people, but the tools to understand and improve it.”

If we value robust civic engagement, we need to find ways to ensure students are informed and involved.

The key to civic engagement

Students are growing up in the Digital Age when, according to Roberts, “social media can instantly spread rumour and false information on a grand scale.” Our children are being continuously bombarded by information from innumerable, competing sources which can overwhelm them and prevent them from engaging with current events and issues deeply.

Incorporating current events into the conversations we have in our homes and classrooms can help us develop our students’ critical thinking, empathy, and curiosity–necessary skills for 21st century citizens.

Make critical thinking a habit.

When students engage with current events, they have the opportunity to practice:

- Thinking about a topic critically and objectively

- Recognizing and appraising an argument

- Evaluating evidence

- Noticing the implications of an argument

- Identifying inconsistencies and errors in reasoning

- Making connections between different ideas

- Considering their own assumptions, beliefs, and values

Critical thinking researcher Tim Van Gelder reminds us that critical thinking is a skill, and like any skill it requires ongoing practice. When we ask students to routinely study current events, they apply core critical thinking skills across diverse topics and mediums.

Cultivate empathy.

In order to help students develop their own understanding of an issue, it is important for them to consider the perceptions of others. In “Teaching Current Events and Media Literacy,” co-authors Karon LeCompte, Brooke Blevins, and Brandi Ray highlight the importance of using current events in classroom discussions. They write, “Students learn to express themselves, challenge one another’s ideas, and revise their understandings.”

Furthermore, studying current events can help develop empathy. Current events challenge students to understand the potentially conflicting perspectives presented in an article. Current events also provide a forum for students to practice their listening skills by seeking to understand the diverse interpretations of their own classmates.

Fuel curiosity.

Questions are the lifeblood of a curious mind. In “Did the Internet Kill Curiosity?,” Sarah Boesveld suggests that while the Internet is likely “the most profound invention in recent times,” it also has the power to rob us of “deep curiosity.”

It doesn’t have to.

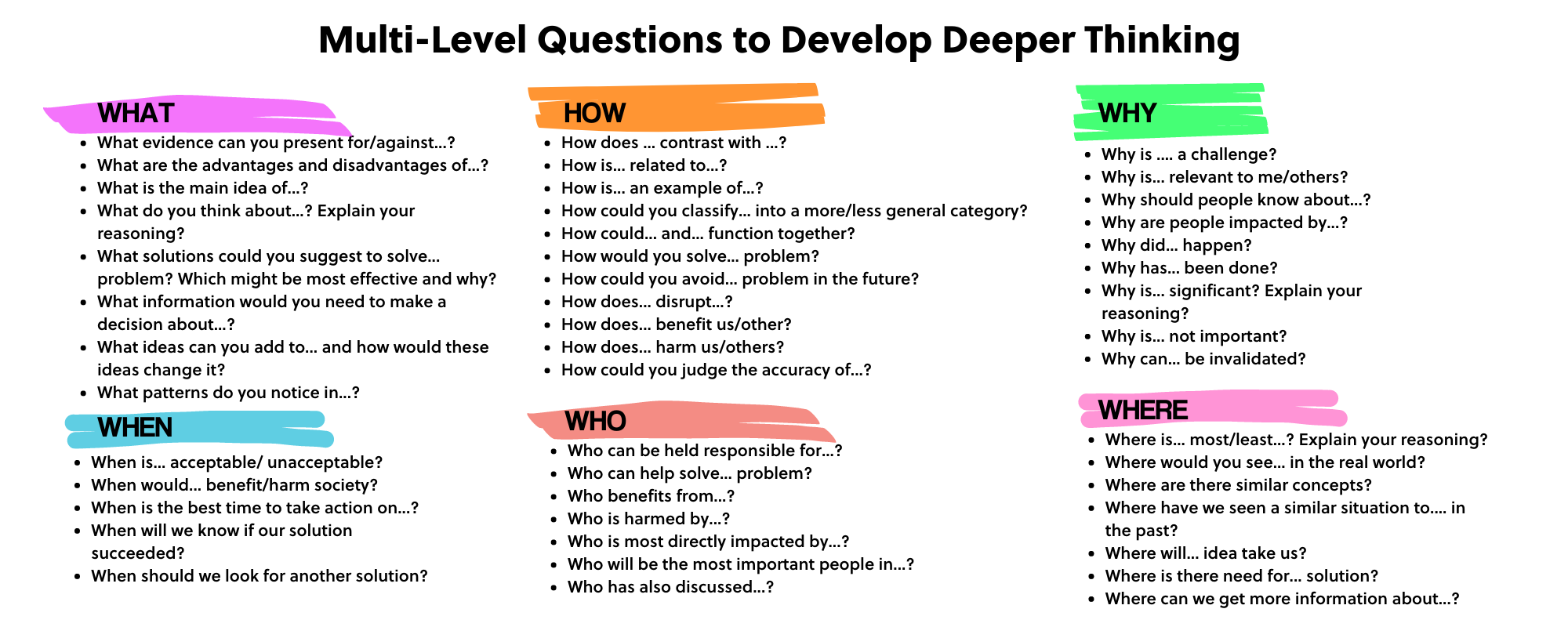

Posing questions is a foundational practice of inquiry-based learning, a teaching model that harnesses students’ innate curiosity to drive learning. When we help our students learn how to ask a range of multi-level questions about current events, we give them the opportunity to read beyond the headlines and to develop a more complex and nuanced understanding of the world.

More than headlines

With the ongoing pressure facing teachers to cover content and improve test scores, fitting current events into the classroom can be challenging. Too often, current event assignments leave students reciting headlines in front of their peers without developing a deeper understanding of the complex issues involved.

Instead, try some of these classroom-tested strategies for teachers and parents.

1. Keep it student-led.

Student investment is critical. Give students ownership and voice in the process. For instance, veteran teacher Megan Selway offers her students a choice of analyzing news stories on the following topics:

- Crime & Punishment

- Energy & Environment

- Economy

- Public Services & Infrastructure

- Individual Rights & Liberties

- National Security & War

After choosing, students are grouped together based on their preferences, thereby allowing them to collectively track current events related to their topic, and collaborate in analysis, question generation, and discussion.

2. Provide structure.

Even if students are interested in the topic, they don’t always know where to start. It’s important to lay out clear guidelines to help students practice the critical thinking necessary to develop a rich understanding of current events. For example, this handout from Project Look Sharp outlines a range of inquiry questions to help students analyze diverse media sources.

Students need a combination of guided learning, independent, and group work to feel supported and to develop increasing autonomy throughout the process.

3. Make time for developing context.

News stories do not exist in isolation. The challenge with teaching current events is that students’ often lack the requisite background knowledge to understand the issue.

Instead of asking students to make one-off presentations, Megan Selway requires her students to follow the same issue for an entire year. She observed that over the course of the semester “students develop an expertise on the topic that allow[s] them to have meaningful discussions in their group and share with their friends, both in and outside of the classroom.”

4. Invite multiple perspectives.

It’s crucial for students to access sources that represent a wide range of views. For example, when curriculum writer and trainer Sox Sperry discussed former 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s decision to take a knee during the national anthem, he asked students to compare multiple sources of information: tweets from President Donald Trump, an NAACP press release, and a town hall discussion hosted by CNN with NFL players, filmmaker Spike Lee, and members of the military. “How does each media form help to inform or to mislead the public by its very structure and the intentions of the authors?,” he asked his students.

We must empower students to seek out these diverse perspectives. Ask them to think about why different groups see the same event in different ways. What is the story that emerges when you bring multiple perspectives into conversation with one another?

Don’t wait

Students need these skills, now more than ever.

In an article recently published in The Atlantic on the state of the American democracy, George Parker argues that we are currently in what philosopher Gershom Scholem called a “plastic hour,” a rare moment in history when popular opinion, current events, and political climate align, allowing “an ossified social order suddenly [to] turn pliable, . . . and people [to] dare to hope.”

In a time of unprecedented civic engagement and unprecedented media saturation and misinformation, students need our help in developing the critical thinking, empathy, and curiosity necessary to build a thriving democratic society.

What we teach now matters. Our students are depending on us.